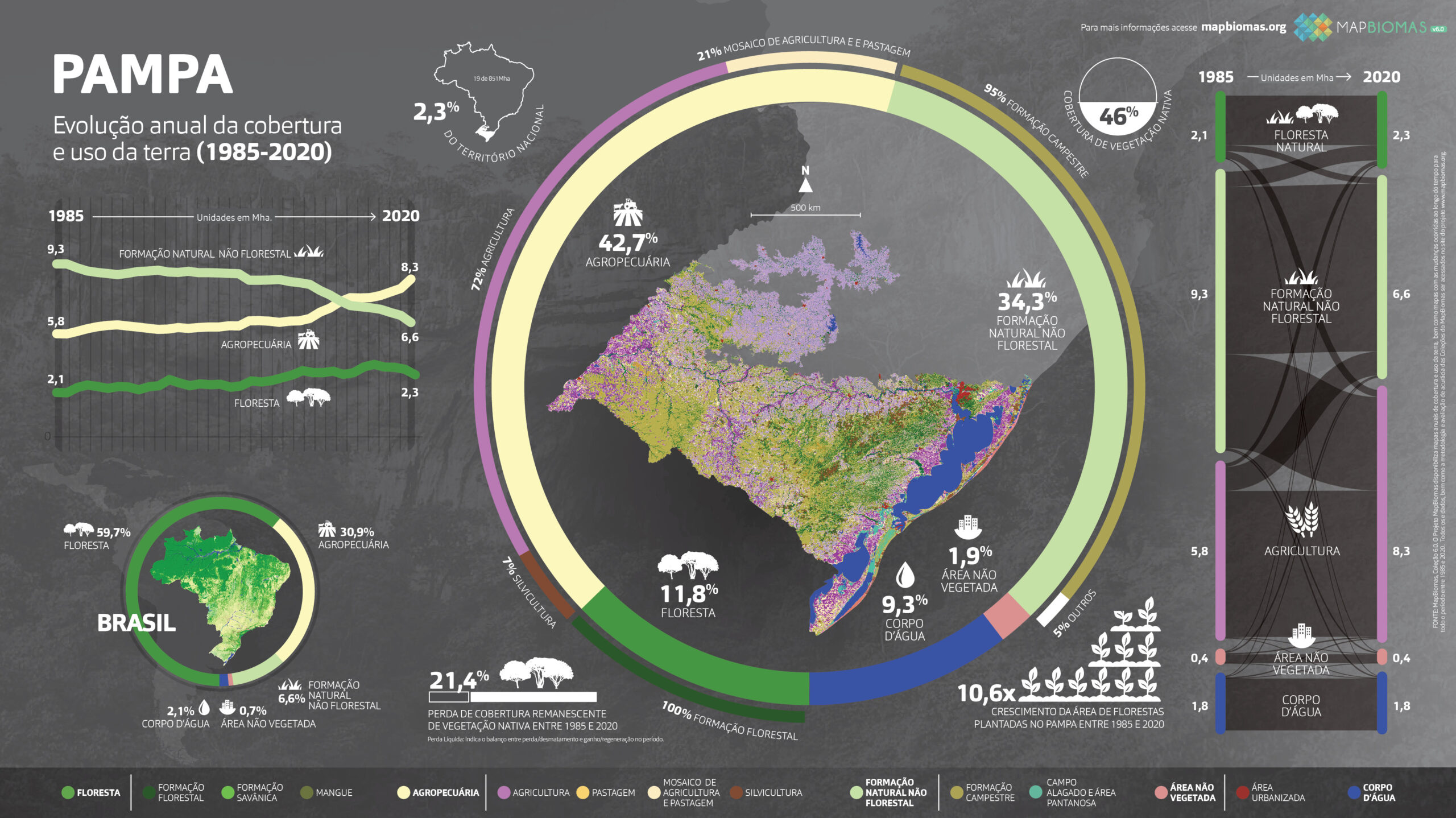

The Pampa biome was the one that lost the most native vegetation proportionally over the last 36 years compared to its total area, according to the latest data from MapBiomas obtained from satellite image analysis between 1985 and 2020. The decrease of 21.4% recorded between 1985 and 2020 puts the second smallest Brazilian biome ahead of the Cerrado (-19.8%), Pantanal (-12.3%), and Amazon (-11.6%). As the Pampa acts as a "hub" for various national and international migration routes, with destinations including North America, South America, the North and Central-West regions of Brazil, and northern Argentina, the conservation of Pampa's natural landscapes is crucial for multiple migratory species.

The Pampa biome, especially in its eastern portion, is considered an internationally relevant region for various species of migratory birds. The presence of a mosaic of natural ecosystems including coastal lagoons, beaches, dunes, grasslands, restinga forests, and swampy areas attracts a remarkable concentration of birds in different seasons of the year, seeking food or breeding sites.

Neartic migrants, species that breed in the Northern Hemisphere (Canada and the United States), fly to the Pampa during the summer in search of food. More than a dozen species are summer visitors, including sandpipers and plovers, also known as shorebirds, such as the American golden plover (Pluvialis dominica), the lesser yellowlegs (Tringa flavipes), the greater yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca), and the buff-breasted sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis).

Southern migrant species fly to the Pampa, where they remain only in autumn and winter. They depart from Patagonia, southern Chile, Tierra del Fuego, and the Falkland Islands towards the Pampa in winter, thus escaping the harsh southern winter. Among these species are the Rufous-chested dotterel (Charadrius modestus), the Buff-winged cinclodes (Cinclodes fuscus), the Rufous hornero (Lessonia rufa), and the Chilean swallow (Tachycineta meyeni).

Other species are summer residents and temporarily leave the Pampa with the arrival of cold months for various destinations. Many head north to South America and Central America, such as the swallows (Progne tapera and P. chalybea), the Fork-tailed flycatcher (Tyrannus savana), and the Tropical kingbird (T. melancholicus). Others migrate east-west to the Argentine provinces of Santa Fe, Entre Rios, and Corrientes. Some waterbirds migrate from the Pampa to the Pantanal, including the Wood stork (Mycteria americana), the Roseate spoonbill (Platalea ajaja), the Snail kite (Rostrhamus sociabilis), and the Comb duck (Sarkidiornis melanotos).

The expansion of anthropic activity on the natural vegetation of the Pampa has intensified in the last decade, coinciding with the beginning of a shift in the economic profile of land use. "The replacement of grassland by agriculture favors biodiversity loss and the release of carbon into the atmosphere, contributing to the greenhouse effect. However, it also represents a deviation from the Pampa's natural economic vocation," warns Heinrich Hasenack, coordinator of the Pampa mapping project. "Unlike the Amazon or the Cerrado, where deforestation is necessary to create pastureland, in the Pampa, native vegetation serves as natural pasture, allowing for the development of livestock while preserving the landscape," he explains. Research results show that proper management practices can provide economic returns similar to grain cultivation, with the added benefit of preserving biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Over the past 36 years, the Pampa has lost 2.5 million hectares of native vegetation, which now accounts for less than half (46.1%) of its territory. Grassland formations occupied 46.2% of the territory in 1985. By 2020, they had decreased to only 32.6%. During this period, agriculture gained over 1.9 million hectares of Pampa land. The activity, which occupied 29.8% of the biome in 1985, expanded to cover 39.9% of the territory by 2020. Last year, it was the primary use of the 44.1% of anthropized land in the Pampa and continues to show a trend of high growth each year.

Conservation units

The Pampa has many grassland species per square meter, even when occupied by cattle, favoring the conservation of biodiversity and stored carbon. Although agriculture, in general, has excellent productivity, in some circumstances it ends up being introduced in locations with less suitability than livestock farming. Another concerning fact is that the Pampa has the lowest proportion of conservation units among all Brazilian biomes, with only 3% of the territory protected. If we discount the Environmental Protection Areas, a category with lower protection level, this percentage drops to 0.6%. There are regions of the Pampa that are already excessively altered, to the point of jeopardizing the very capacity for ecological restoration with the genetic variants typical of these regions.

"Despite being part of the Gaúcho tradition, in the history of biome occupation, and being an activity that, in the Pampa, is more aligned with the 21st-century challenges of biodiversity preservation and carbon emission reduction, livestock farming on native grasslands is losing ground to agriculture, notably soybean cultivation," details Hasenack.

The advance of agriculture on native vegetation can be observed throughout the biome, but it was more pronounced in the regions of the West Border, Middle Plateau/Missions, Coastal Zone, and east of the Campanha. The five municipalities that lost the most natural vegetation in the last 36 years were São Gabriel, Alegrete, Tupanciretã, Dom Pedrito, and Bagé.

The mapping results of the biome also provide unprecedented data on wildfires and water surface. In the Pampa, unlike other biomes, wildfires have little significance with an annual average of 92.5 km2. Several factors contribute to explaining the low occurrence of wildfires in the Pampa, such as the absence of a dry season, low biomass accumulation in the grassland vegetation due to pastoral activity, and the fact that fire is not culturally used as a management practice in rural areas.

The dynamics of water surface between 1985 and 2020 show a trend of stability over the mapped 36 years. Nearly 10% of the Pampa is occupied by water, with 1.8 million hectares in 2020. Most of it is concentrated in the coastal zone, characterized by numerous lagoons, with Laguna dos Patos, Lagoa Mirim, and Lagoa Mangueira holding 81% of the total water surface in the Pampa biome. Despite the stability in water surface, the mapping reveals that in the regions of the Western Border and Campanha, there was an increase in water due to the implementation of reservoirs for irrigation, mainly for rice cultivation. Meanwhile, in the central and eastern portions of the biome, several areas with reduced water surface were detected.

About MapBiomas

Multi-institutional initiative that processes satellite images with artificial intelligence and high-resolution technology in a collaborative network of experts, universities, NGOs, institutions, and technology companies for the creation of historical series and mapping of land use and land cover in Brazil. UFRGS, with the collaboration of GeoKarten, are the institutions responsible for mapping native vegetation in the Pampa biome within the MapBiomas network.

Access the main highlights of Collection 6 of the Pampa biome.

Download the infographics here:

Find out how the presentation of Pampa data went: